A month ago, the worst fears of a coronavirus housing apocalypse were coming into view: According to the National Multifamily Housing Council, 31% of renters living in 11.5 million apartment units in the U.S. were late on the rent on April 5. That figure didn’t include the tens of millions of renters who live in single-family homes and other housing situations.

But by hook or by crook, millions of American renters made it through April. By April 26, the share of apartment tenants who were late with the rent had fallen to 8% — enough to put the month just a few percentage points behind rent collection in March (95%) or April 2019 (96%).

Now comes May, and the national unemployment rate has surged, reaching as high as 22%. To make sense of how deep the coronavirus housing crisis really runs and what might happen this month, CityLab asked readers to submit their most pressing questions about keeping a roof over their heads. Tenants and landlords alike sent in their thoughts and concerns. Some of these questions with answers follow (in condensed form).

Q: Are renters going on strike?

A: Yes. The national #CancelRent movement that took shape before May Day may be the largest rent strike in decades. Tenant organizers drummed up support for actions in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, New York, and other cities.

We Strike Together, a joint partnership by a number of social justice organizations, counts more than 190,000 rent and mortgage strikes. In New York alone, the Upstate/Downstate Housing Alliance garnered more than 14,000 commitments to not pay the rent or mortgage, including some 57 apartment buildings.

Q: How many people paid rent for May?

A: There’s no way of knowing yet. If April was any indication, there won’t be a true answer for a while.

Last month, people reached deep into savings or paid with credit cards. Some out-of-work tenants began receiving unemployment benefits; others are still on hold. Some people are now getting state-level benefits but not the $600 federal boost. Millions are waiting for their federal stimulus checks to arrive, but this is only a one-time payment — and $1,200 doesn’t even cover the average rent for a two-bedroom apartment anywhere in the country.

With so many people struggling, landlords may not be in a hurry to evict their tenants, according to Flora Arabo, national senior director for state and local policy at the nonprofit Enterprise Community Partners. They may be willing to work with renters on partial rent or repayment plans in order to keep some income flowing.

“Most housing providers don’t want to have to evict tenants,” Arabo says. “They want steady tenants who pay. For most providers, it’s a last-resort option. If there is a massive wave of evictions, that’s not good for the property owners either.”

Q: Can renters be evicted during the pandemic?

A: The answer depends on a couple of things: where renters live and what kind of mortgage their landlord has.

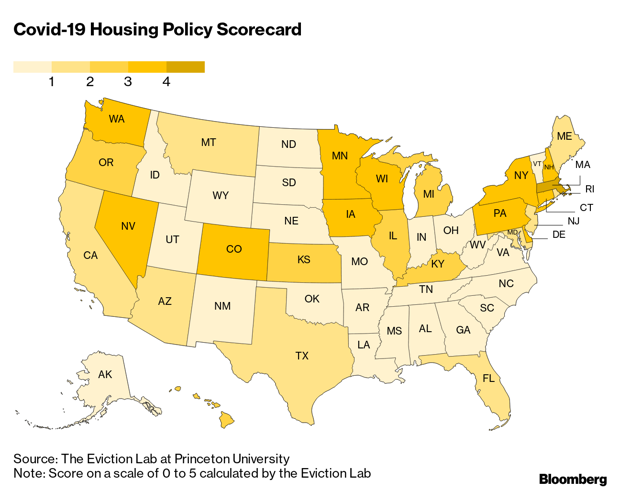

States are all over the map on coronavirus tenant protections. Six states have taken no action (or next-to-no action) during the pandemic: Arkansas, Idaho, Wyoming, North Dakota and South Dakota. None of those states has passed any kind of statewide order to prevent evictions or foreclosures during the pandemic.

Other states have done only the bare minimum in terms of tamping down coronavirus evictions. In Oklahoma and Georgia, for example, the states have extended deadlines for eviction proceedings. Those states are still conducting court hearings, but in most states — even those with limited tenant protections, such as Louisiana and Virginia — the courts are closed.

Princeton University’s Eviction Lab has produced a helpful scorecard for each state based on their Covid-19 housing policies. On a five-point scale, Massachusetts earns a 4.15, the highest score in the land; Georgia merits a whopping 0.08 (still better than some others). The National Consumer Law Project also offers detailed guides on eviction moratoriums for each state.

Some cities have produced even stronger rules about evictions and foreclosures. There’s no central database for where cities stand yet. But any city that is willing and able to pass tougher regulations on landlords is likely to have a tenant advocate or another office that can provide more information.

In April, a national bill to cancel and forgive all rent and mortgage payments for the duration of the crisis was introduced by Minnesota Representative Ilhan Omar. For now, though, renters still owe the rent, no matter where they live.

Q: Does the landlord’s mortgage affect whether renters can be evicted? And how can renters get that information?

A: Renters who live in a property backed by the federal government cannot be evicted for the time being. This eviction moratorium applies to a vast web of mortgages financed, insured or securitized by federal agencies (such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) as well as homes subsidized through federal aid programs (like Section 8).

For tenants in apartment buildings, there are a few tools available to figure out whether the eviction moratorium applies where they live. On May 4, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac both launched look-up tools: Renters can enter their building name and address to find out whether the property is federally backed. The National Low Income Housing Coalition put out a similar tool in April.

However, these tools won’t help the tens of millions of renters who live in single-family homes. The Federal Housing Finance Agency is working on that tool, but for now, renters in single-family homes, condos, and small apartment buildings will need to talk to their landlords to find out whether their units are covered by the eviction moratorium laid out by the CARES Act.

Q: What happens if my lease ends while shelter-in-place orders are in effect? What about renters who don’t have written leases?

A: Under normal circumstances, the lease itself describes what happens when the lease ends, whether it expires, renews for a certain term or converts to a month-to-month agreement. State laws outline default procedures for circumstances when the lease isn’t specific. A stay-at-home order would not block a lease from expiring or renewing. But a federal, state, or local eviction moratorium would stop a landlord from removing a tenant or a leaseholder from kicking out a subletter.

“Even if a tenant’s lease has expired and the person hasn’t moved out, the landlord is required to take the tenant to court and cannot lawfully resort to ‘self help’ such as changing locks or disconnecting utility service,” says Eric Dunn, director of litigation for the National Housing Law Project. “It’s kind of a legal twilight zone where the tenant may not have the ‘right’ to possession of the premises, but does have the right not to be evicted except through judicial means.”

So it comes down to the eviction moratorium. Under the CARES Act, landlords have to give tenants a 30-day notice to evict after the moratorium expires. Many of the state and local moratoriums don’t have this buffer, so tenants without a lease could be out as soon as the order expires.

Landlords may not be in any hurry to see their tenants out the door. In fact, the opposite might be true: Landlords (or lease-holders) may ask tenants (or subletters) to sign full-year leases right away in order to guarantee the rent.

Q: Is there any sort of housing assistance to help out with the cost of rent during Covid-19?

A: In some places, yes. For example, in Massachusetts, a program called Rental Assistance for Families in Transition provides up to $4,000 for households in distress, and the state added $5 million in funding for households affected by Covid-19. In Dallas, more than 16,000 people flocked to apply for rent and mortgage assistance on Monday, the day the city opened its program.

Housing experts are calling on Congress and federal agencies to do a lot more to make aid for renters available everywhere.

Q: Due to the pandemic, some renters can’t use building amenities like gyms, lounges, courtyards, and roof decks. Can renters ask for partial coronavirus rent abatement?

A: Maybe! But before you ask, you might want to remember that many landlords report spending more on maintenance costs, hiring cleaners ‘round the clock to scrub mail rooms and common spaces. Rent abatements are subject to normal lease rules. Rent increases are frozen in a few cities and states for now.

Q: What can landlords do if their tenants can’t pay the rent? What about homeowners who can’t pay their mortgage?

A: More than 3.8 million homeowners are now in mortgage forbearance plans — which is more than 7 percent of all mortgage holders.

Homeowners and landlords with federally backed mortgages may be able to defer their mortgage payments for up to a year, with no added interest, late fees, or penalties. The National Consumer Law Center has assembled a guide for property owners to determine whether their homes or buildings are federally backed or insured.

The federal government is offering the best possible terms for mortgage forbearance. Banks are offering their own forbearance plans, however, often with terms that are less beneficial for borrowers.

Hello Lender, a tool for mortgage borrowers experiencing financial distress, auto-generates a letter to lenders to declare the homeowner’s participation in the federal forbearance program. The free tool — a product by Six Fifty, the technology arm of the law firm Wilson Sonsini — works a little bit like TurboTax. Borrowers enter their information, and the tool spits out a letter with all the qualifying information.

Q: How can renters get their landlords to work with them on the rent? What if the property owner is a corporation or real estate investment trust?

A: Six Fifty offers another tool, Hello Landlord, for renters to issue notices to landlords that outline tenant rights under state law and the CARES Act. Written notice might be the best approach to take for renters living in large multifamily buildings owned by a corporate landlord.

Nobody knows what happens when eviction moratoriums expire. When the $600-a-week federal expansion to unemployment benefits expires in August, it could trigger a massive wave of delinquencies for out-of-work renters and borrowers. At the same time, a wave of evictions could be followed by a glut of rental vacancies, which doesn’t serve landlords’ interests.

Short of sweeping rent strikes, many housing experts encourage renters to call their landlords, explain their situation, and see what they can work out. “Renters are responsible people,” Arabo says. “They want to pay their rent. They don’t want to lose their housing.”