Among Lisa Yuskavage’s earliest, if rarely seen, works are some drawings of men, which frankly have more in common with Otto Dix and his brethren than much else. With her treatment of light and shadow, they are so damagingly psychological that they seem as ruthless as they are tender in their honesty. I can’t tell if these are good men or bad men, and the desire to classify them as one or the other only arises because there is a surety in the flat line of their lips that smacks of the nonchalance seen in people rarely reprimanded for things like talking or acting; they have the look of a person who assumes their experience means more than the rest.

It’s fascinating to see these drawings within the context of the paintings for which Yuskavage is so known—those sexually hyperbolic paintings of buxom female bodies—as the two don’t seem to go together. The men in those early drawings are too serious to exist in one of her pugnaciously female-forward paintings. As is her technique: The gestures in these works feel hazardously quick, as if she were in the act of catching some truth that might escape if she paused her hand. It’s a far cry from the laconic, lusty atmospheres of supernatural light seen in her large canvases—those quick lines have real cinematic suspense, and you feel like you’re looking at something that maybe everyone was supposed to miss. Yuskavage wouldn’t paint a man again for decades.

These drawings are also notable because Yuskavage, along with a spate of other artists, has made headlines for depicting men. “Painter Lisa Yuskavage Goes from ‘Vulgar’ Women to Saintly Men,” The Wall Street Journal announced in 2015, noting works with titles like Dude Looks Like Jesus, and others showing men as hippies, nestled with their families. Likewise, compelled by the recent outcry against men, John Currin departed from his hypersexualized portraits of women to consider the male experience, specifically as it resembles his own. Last year, a museum exhibition at the Dallas Contemporary was devoted to this endeavor, titled John Currin: My Life as a Man. And this spring, Cindy Sherman will debut an exhibition of androgynous self-portraits at Metro Pictures this September. It’s a groundbreaking series of undeniably elegant works: In one, Sherman wears a T-shirt silkscreened with an image from her cinematic 1980–81 Rear Screen Projections series, in which she rendered herself alternately as a middle-aged woman, a kidnapped girl, and a femme fatale. The Sherman wearing the shirt—all short, silver-flecked hair, side-parted and slicked back, hands pushed into the pockets of a loose camel-hair coat—looks back at us with amused interest. It’s an expedient, comic contrast, but one unified by, in Sherman words, “a love of a character.”

One might sense a pattern emerging, if only due to the late revelations that many powerful men have a shatterproof ability to purchase sexual impunity. Contemporary artworks certainly shed light on their current political moment, though the point of great art is that it withstands time. If art is vital for its ability to illuminate ruptures in the popular imagination, this pattern might indicate that the straight, white male has finally become flat enough to be an object of fascination—as opposed to a representation of power. It signals that our era has opened the space to see his experience as perplexing, potentially dangerous, so much so that he, too, is worth being examined, scrutinized, and objectified.

In an earlier age, this was the job description of the muse, an object of lust for her pernicious contradictions—innocent and seductive; grotesque and beautiful; corrupt and virtuous; human but not human. Or it could also be the description of the joker, another figure who understands those polarities. In the context of daily life, the muse and the joker might recognize a vulnerable quality in each other, that painful expectation of being looked at without being seen. It is not terribly surprising, then, that the clown and muse have been significant subjects in Sherman’s oeuvre, their spirits writ large in these new works, both underscoring the way we shift ourselves to fit within our cultural canon. And yet what makes this new series so exceptional is that it indicates, however subtly in its lack of stock femininity, that the canon itself may have shifted to us.

To be sure, if Sherman has become iconic in popular culture for her representations of women, this new series, all dye-cast sublimations on large sheets of metal, is certainly not the first time she has explored androgyny. In 1980, Sherman and her then-partner, Richard Prince, took photographs of each other, both wearing the same wig (an auburn 1980s New Wave bob) and outfit (white shirt, black suit jacket—more Saint Laurent than masculine). They appear side-by-side as a diptych, each image a tightly cropped close-up, with their faces illuminated by chiaroscuro light. If the Helmut Newton androgyny of it all is honest to the gender dynamics of the Bowie era, the smallest but unmissable details go beyond any cosmetic stylization. In 2003, it was Sherman’s clown series that wiped away gender, depicting her face layered in masks of paint, leaving her recognizable only by her two piercing eyes, human to the point of universal: Each feels like a remnant of a being, small embers that might burn if touched. All these instances took notions of identity beyond politics, or, in the artist’s words, “reinforced sympathy” to a larger plight by “showing a bit of rebellion.”

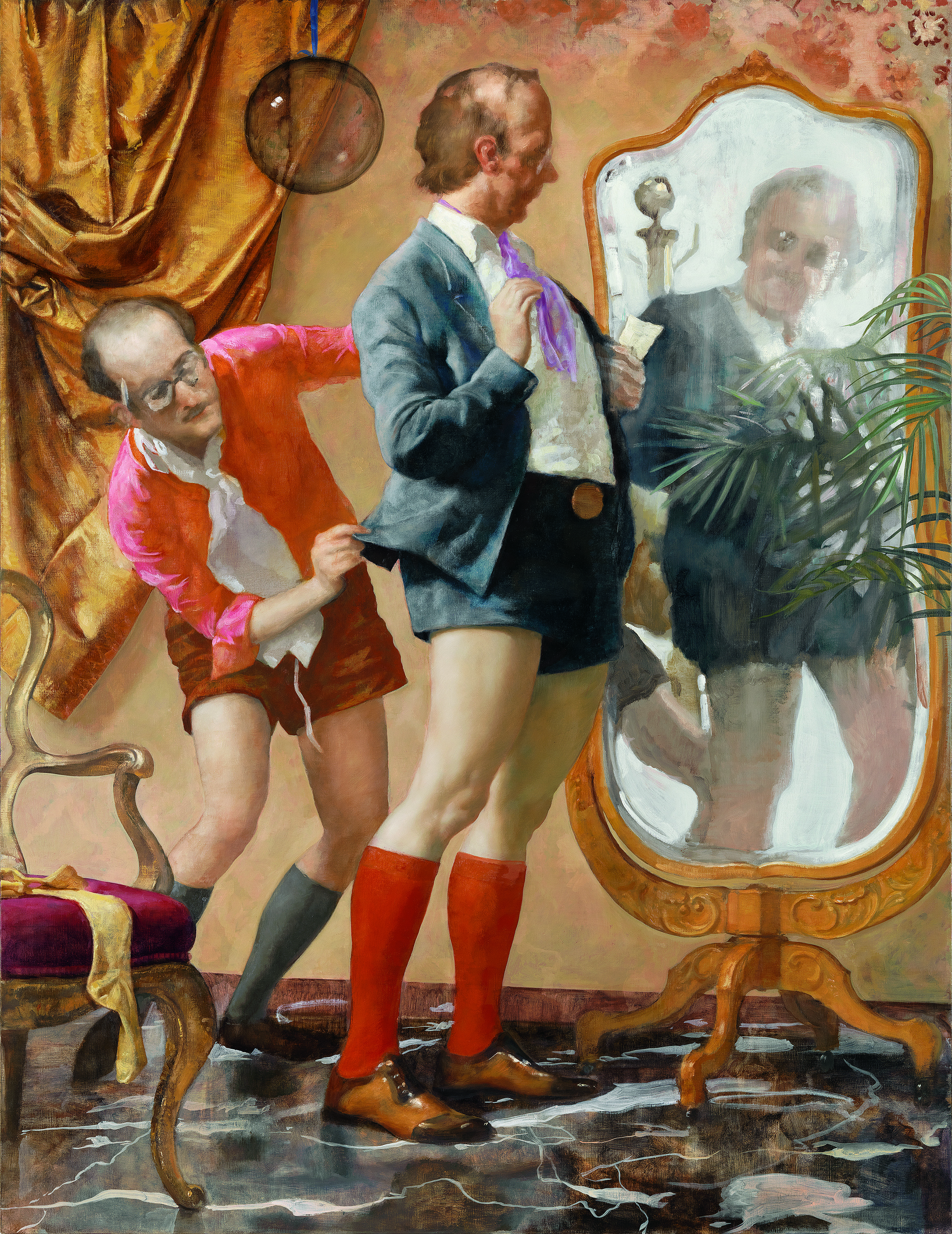

Some decades ago, John Currin debuted grand paintings of busty nymphs with come-hither poses, laying the foundation for a resplendent career. In all their bright brutality, those technically masterful paintings contained an honesty of a culture directed and produced by men. His new body of work, however, is different: The images depict sweet, dashingly aged men. They are happy at the breakfast table, adoring their wives, as if the satisfied man is the benevolent man. Their atmospheres evoke silly moments of hubris: Alison Gingeras, who curated My Life as a Man, pointed out that the critical strength in this body of work is in the way it illustrates the straight, white man’s capacity to notice his own foibles, moments of vexing vanity.

If Currin is imagining the costs of self-realization that men face in a polarized climate where the culture has turned against male hegemony, the price depicted here seems to be an awareness of things like age, the ample woman at their table, the girth of their flesh. In Hot Pants, a man examines his suit, comically noticing the pudge that comes with an older, well-fed body. Currin has stated that these portraits were made reflexively, in response to the inequities giving rise to the #MeToo era. It would be thrilling to see Currin, undeniably one of the most proficient painters working today, insert these men into a more marginalized arena—perhaps subject one of them to the experiences of those who are objectified by men (in other words, those who look awfully like the women Currin paints).

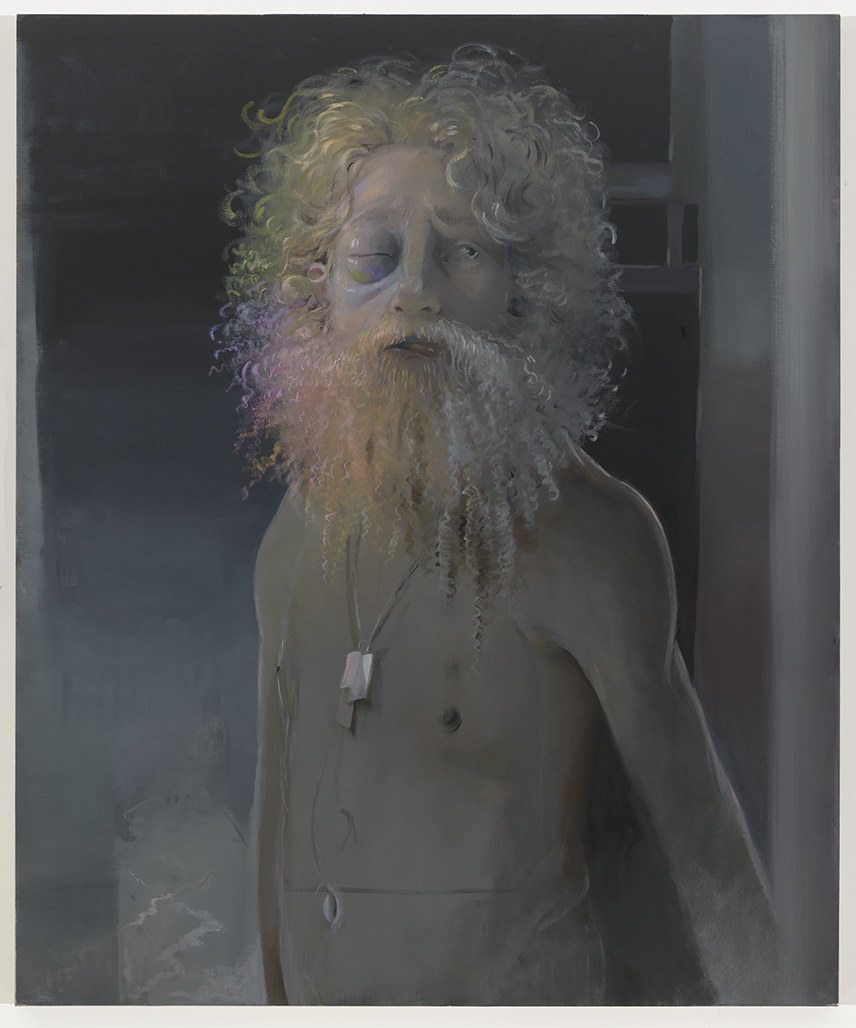

If Currin’s portraits of men lack the vibration of his voracious portraits of women, maybe it’s simply the trap history has set for those born of a certain privilege. Looking at these works in the context of Currin’s oeuvre, I think of a line from a letter written in the early 19th century. One son wrote to his sister of their gentry father: “A man full of bitter criticism for the party he is in greatest agreement with can never acquire any real influence.” One of the things that made the diptych of Cindy and Richard, and Yuskavage’s Man’s Head from 1989, so great is that it’s difficult not to experience the love of looking when staring, because in all their contradictions, their rampant ambivalence to identity, each was tarnished enough to belong to anyone. To quote Sherman: “Subjects and depictions are best left ambiguous.”